For some people, prison is temporary. At some point, they get released, they go home, and they move on with their lives.

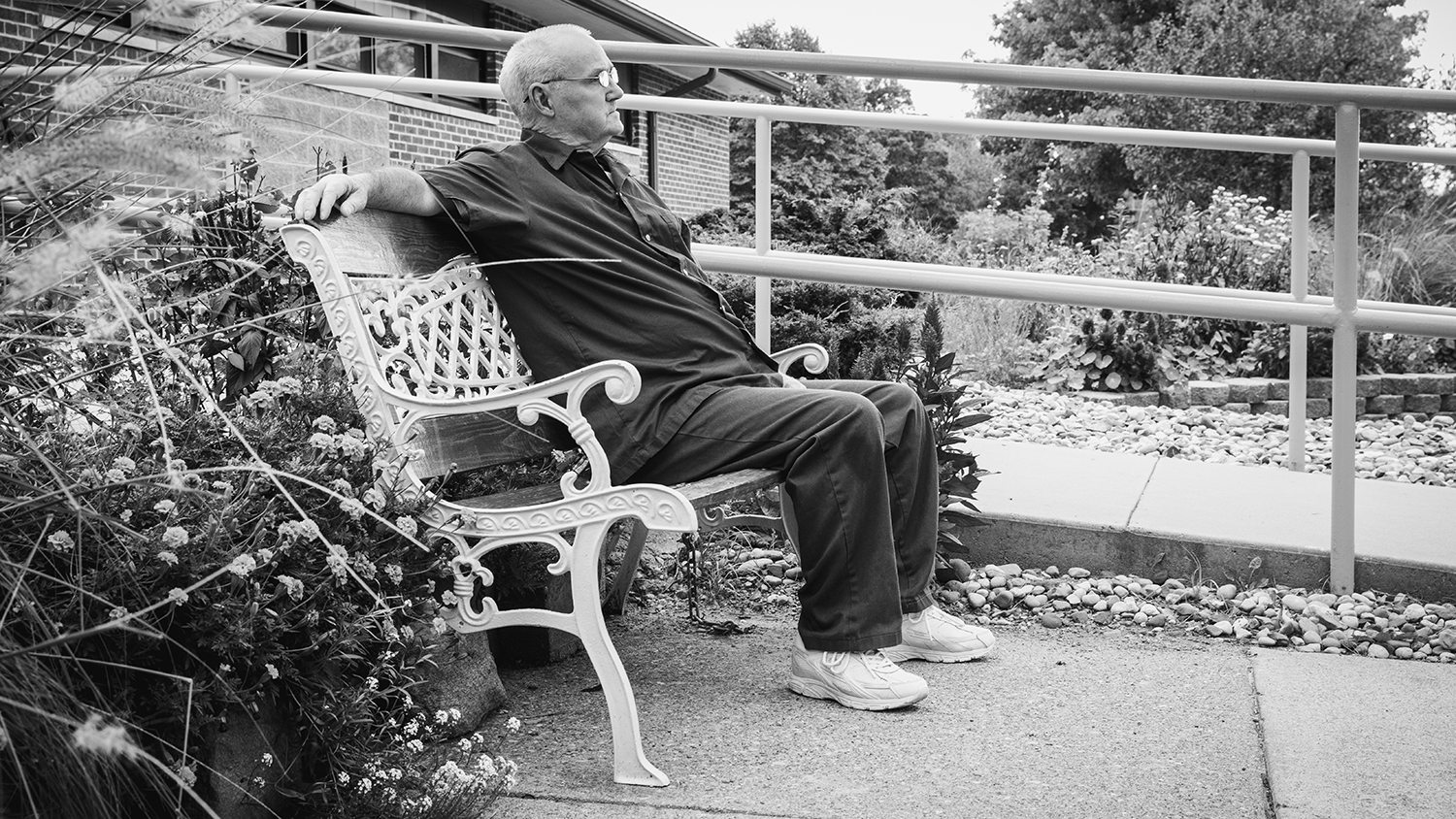

But for those serving a life sentence, prison is their home. And whatever meaning they can find in life will have to be found behind the barbed wire and prison walls.

That is the reality for a large percentage of the inmates at Lakeland Correctional Facility. More than 45 percent of the men there are serving life sentences. That’s the highest concentration of lifers in any Michigan prison.

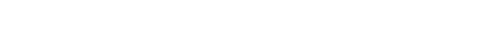

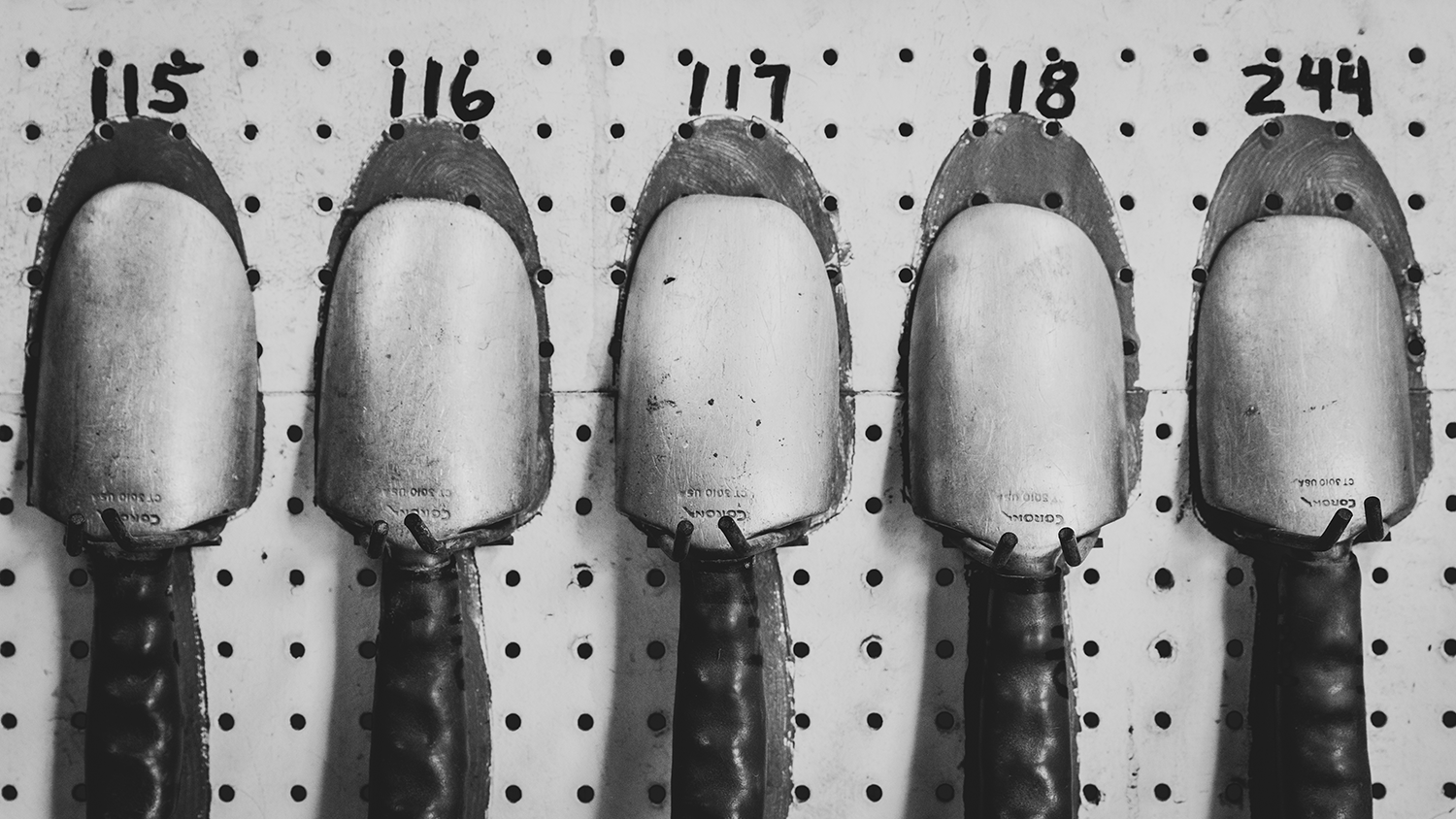

This fall, a dozen Michigan Radio and Stateside reporters and photographers spent the day at Lakeland. The team was given unprecedented access.

Below, you’ll hear the stories of the men serving life in prison there, and what life on the inside is like for them.