What are prisons for? Some see prisons as punishment, even vengeance. Others see them as a means to keep the public safe. More recently, prisons have become an opportunity for rehabilitation.

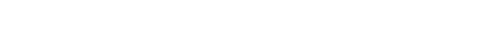

In our special series, “Life on the Inside,” Stateside examines Michigan’s prison system — what it is, what it could be, and what some say it should be.

All this week, we’ll take you inside Coldwater’s Lakeland Correctional Facility to speak with those who live or work there. But first, we speak with historian Heather Ann Thompson, who was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for her book Blood in the Water, which covers the Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and its legacy.