When you’re sent to prison, many of the things that make life meaningful — work, family, friends — are gone. During Stateside’s visit to Lakeland Correctional Facility, in Coldwater, we wanted to know how inmates there create meaning for themselves.

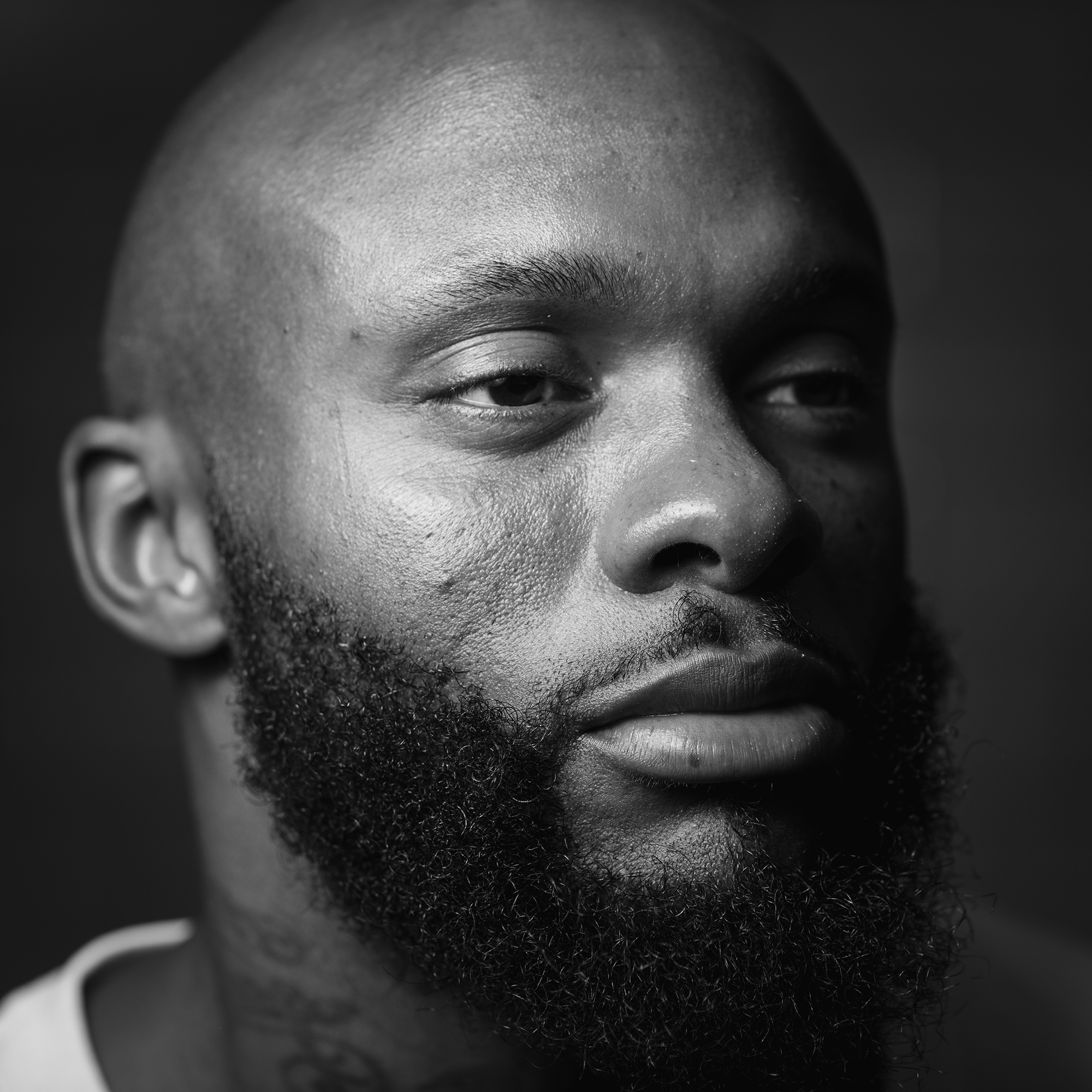

To do that, we talked to two of the men there — Matt Blumke and Felton Mackiehowell — during our live show at the prison.

Blumke is 39 years old, and worked as a photographer before being incarcerated six years ago. Mackiehowell, who is 30 years old, describes himself as a “writer, artist, and poet.” He has been incarcerated since he was 19 years old. Both men aren’t eligible for parole until after 2030.